Šid, November 14th, 2015

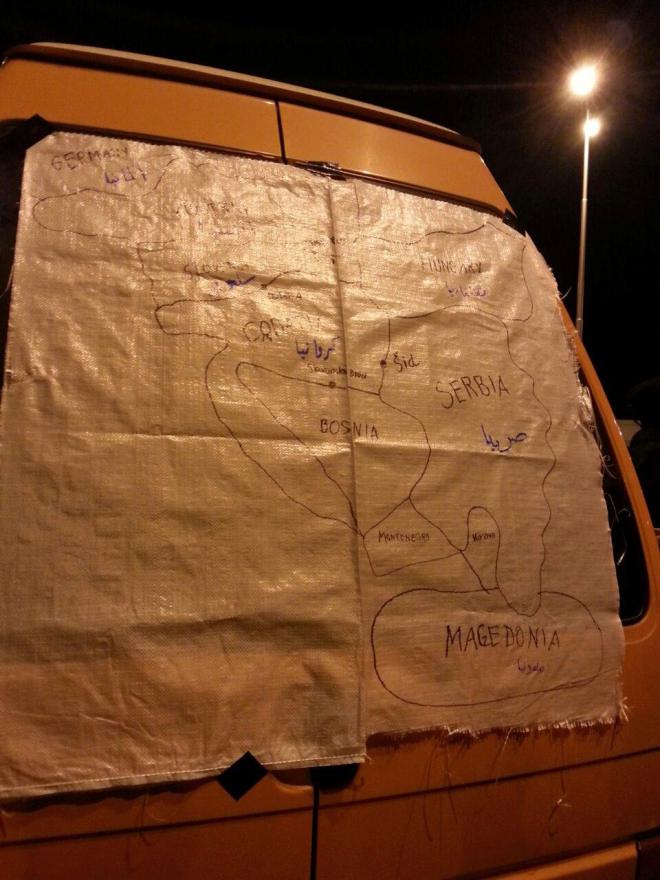

The Moving Europe bus is a project by Welcome to Europe, Forschungsgesellschaft Flucht und Migration and bordermonitoring.eu. The aims of the bus are to document the situation on the Balkan route, to provide information for people on the move, and to strengthen political networks along the route.

Petrol station in Adaševci, Serbia, in the evening

Around 20 people press themselves against the glass doors of the shop of the petrol station in Adaševci. Serbian police officers are standing in front of the doors that usually slide automatically open and welcome customers. The cops gesture aggressively: „Closed.” The fact that the petrol station is only closed for some is revealed by its glass front. Some people wearing vests of big humanitarian organizations, police officers in their coffee break and few migrant families, that managed to get inside, are seating on the other side of the window. Being asked why the doors of the shop are closed for some, the police officers answer „Because people steal.” Here it is: The powerful creation of fear of the Others, who would steal ‚our‘ jobs or turn the local park into a drug-dealing-zone. And loot the petrol station. At the same time it seems that the petrol station makes good profit on that evening: Some minutes before, one person who managed to get inside, had been charged 40 Euros for two packages of biscuits and two bottles of Coke. One woman with a baby in one arm directly turns to one of us, and hands over some Euro notes: „Go inside for us, my child needs water.” The racialised segregation is more than obvious. For us, as white Europeans, the doors to consumption are open. In this moment it doesn’t matter whether those outside have money or not. Of course, those without any money are not even struggling to enter the shop. They are gathering around the corner and bottle water from the taps, as the humanitarian organizations have already closed their distribution tents. A journalist accompanying a family on their way from Syria through the Balkans, remarks that the petrol station turns into an image of Europe.

Train station in Šid, Serbia, few hours before

The three young men lean against the open door of the coach, chat with each other, smoke, and beckon to us to come closer. The vehicle is parked behind 15 other coaches in front of the train station in Šid. People are waiting to get on the trains to Croatia. The atmosphere is tense, shortly before we arrived the police has pushed them violently back into the coach. „We didn’t get water now for seven hours“, reports one of them. How is this possible? We refuse the money the young man tries to give us for bottles of water. Instead, we turn to the small container, where the people with blue UNHCR vests gather. After a short and friendly conversation, we move back to the coaches with dozens of water bottles. As we pass by the row of coaches, people from another coach also state that they are thirsty. Back at the UNHCR container, we request more water for the other coaches. This time, the conversation is less friendly: When handing out too many bottles now, there won’t be any water left for later. And distributing only a few bottles in one coach would provoke conflict and chaos.

We struggle to understand the situation: Is the UNHCR not able to drive to the nearby supermarket and buy more water? Are people supposed to be left thirsty? Very soon, our presence is being put into question: “Do you have a permission to be here?” The UNHCR points to the local Commissariat, which is coordinating access of groups and NGOs to the field. That’s how the journey of human beings to Western Europe is described in the language of (Non-)Governmental Organizations. With the chief of police in his back, the representative of the Commissariat makes it clear: No accreditation, no right to be here. We are banned from the area around the train station. No surprise to us – two activists have just reported their day-long struggle with the Commissariat to set up an information point in Adaševci, the petrol station where coaches are waiting for several hours before departing to the train station.

Exclusion of independent observers and civilians

This is what we have encountered frequently during the last days, while trying to access camps and transit zones. Civilians who try to approach the corridor to Western Europe controlled by the police are granted access only with an accreditation, for which they have to apply formally. This happens through (most of the time: state) authorities. It is very clear that this accreditation system is just a system of control. A system of control that is regulating the access of independent observers and other critical voices. The migration corridor is an attempt to manage and control the power of migration. This corridor is surrounded by a semi-public space, which is supposed to be controlled by state forces and NGOs.

Paradoxes of (N)GO logic

At the same time we perceived a lack of basic supplies like water or food. Paradoxically, individuals or NGOs are coming with vans full of food, clothes and drinks, but are not allowed to hand them over as only few managed to obtain the accreditation from the Commissariat. Our attempt to register an information point in Adaševci was rejected. However, similar refusals do not only happen to activist groups and small NGOs: We have met members of an international, widely recognized NGO, that were about to leave with hundreds of lunch packages. At the same time migrants are reporting repeatedly that they didn’t get any water and food for hours. The UNHCR seems unable or unwilling to provide enough supply for the number of people on the move. Why does the UNHCR act like this? We do not understand this artificial shortening of supply.

In our perception, the restrictive accreditation procedure leads to a situation in which only very few NGOs are allowed to be present. The small – and critical – organizations that managed to go through the registration process are constantly pushed to their limits. There is a clear monopolization of access happening through the UNHCR and the Commissariat. The situation that we have encountered here indicates that those organizations are just processing, controlling and administering migrants. The needs of human beings are not of any importance. They perform an authoritarian humanitarianism: Legitimizing a statist logic through the presence of humanitarian organizations, it assures the efficiency of control at the same time. But these attempts of control fail constantly – those on the move don’t accept to be treated as mere objects of control or care.